Security Council Open Debate on the Maintenance of International Peace and Security, May 2018

Prepared by Ijechi Nwaozuzu

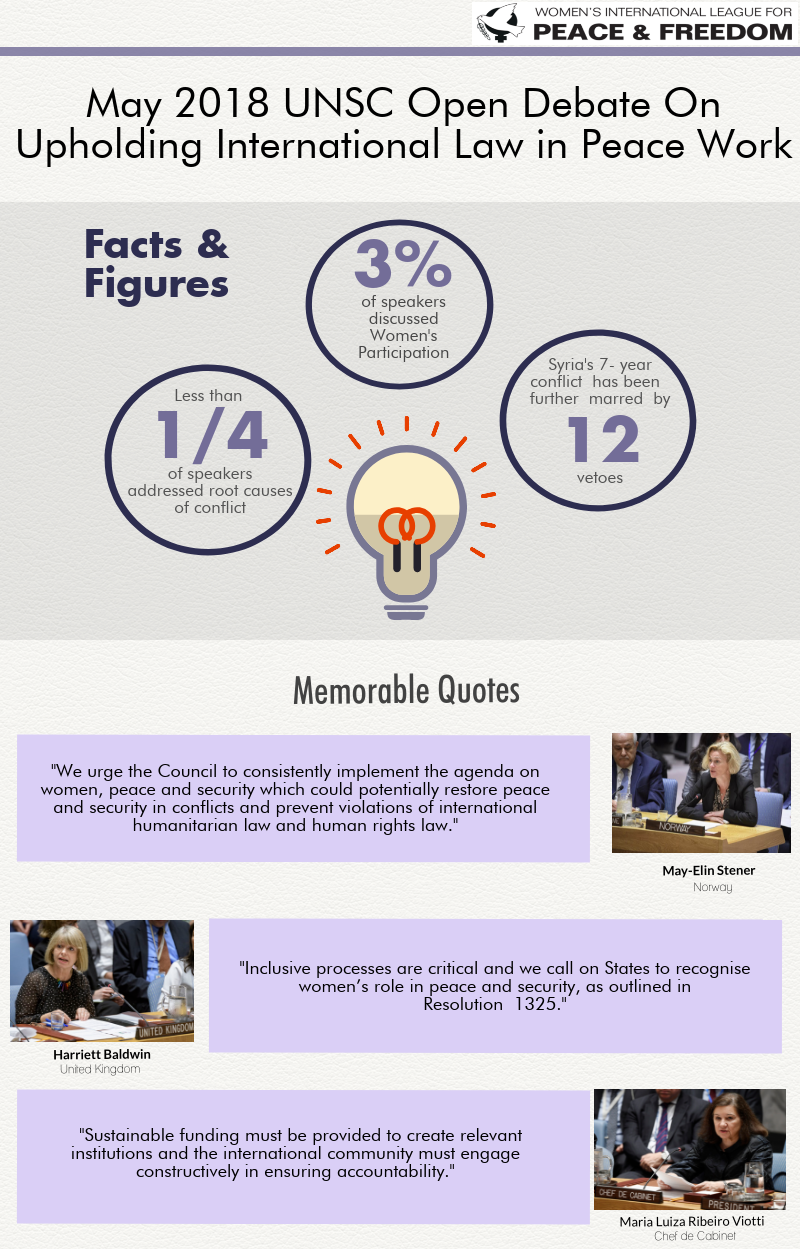

Maria Luiza Ribeiro Viotti, Chef de Cabinet to Secretary-General António Guterres, addresses the Security Council meeting on the maintenance of international peace and security, with a focus on upholding international law within the context (UN Photo/Evan Schneider)

Overview

On 17 May 2018, under the Presidency of Poland, the Security Council held an open debate to reflect and improve on the status of international law under the agenda item “Upholding international law within the context of the maintenance of international peace and security”. The debate was framed as an opportunity to consider the Council’s role in upholding international law through: promoting the peaceful settlement of disputes; respecting international law during conflict, as guided by the Geneva Conventions and UN Charter; and upholding accountability. In particular, many speakers expressed positive anticipation for the activation of the International Criminal Court’s jurisdiction over crimes of aggression on 17 July 2018. However, apart from miniscule references to women’s participation and ending impunity for sexual violence, the debate was predominantly gender-blind. Contrary to expectations, the debate failed to address the ICC’s role in prosecuting gender-based persecution and torture by the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL). Speakers also failed to utilise existing gender jurisprudence from the ICTY and ICTR to address remaining gaps in international jurisprudence in conflict.

Highlights

Chef de Cabinet of the Secretary-General, Maria Luiza Ribeiro Viotti, focused her opening statement on the importance of the role of the International Court of Justice (ICJ) and other international tribunals like the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia (ICTY) and the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR). Specifically, she called for the Council to increase its engagement with these mechanisms and for more Member States to accept the ICJ’s compulsory jurisdiction. She praised the formation of other similar criminal courts like the MINUSCA-supported Special Criminal Court in the Central African Republic and the Hybrid Court in South Sudan. Like other speakers, she called for the establishment of similar UN-facilitated courts in other conflict countries, including an independent investigative team in Iraq to hold ISIL accountable for crimes against humanity.

Other key suggestions to combat impunity for mass atrocities included the restriction of veto powers for crimes involving mass atrocities and the effective implementation of Resolution 2368. The representatives of Ireland, Mexico and Belgium reaffirmed their support for the Franco-Mexican initiative to restrict veto powers for situations involving mass atrocities and crimes against humanity. Others speakers expressed similar concern for Russia’s use of 12 vetoes throughout all 7 years of the Syrian conflict and how it continues to compromise the Council’s legitimacy. Meanwhile, the representatives of Switzerland, Argentina and Slovenia called for an immediate appointment of an Ombudsperson for the Office of the Ombudsperson to the ISIL (Da'esh) & Al-Qaida Sanctions List, in line with Resolution 2368. The representative of Austria argued that the vacant post, which has not been filled for 9 months, has allowed further impunity for mass crimes in Syria and Iraq by ISIL members.

Apart from considering steps towards facilitating investigations, prosecutions, due process and witness protection, a few speakers spoke on prohibiting the use of weapons of mass destruction (or “WMDs”) as a viable means to prevent conflict. For starters, the representative of Belgium commended the addition of 3 new forms of international crimes to Article 8 of the Rome Statute, which includes: microbial, biological or toxin weapons; weapons that injure by fragments undetectable by X-rays; and laser weapons. In a similar vein, the representatives of the United Kingdom, Poland, and Lithuania condemned the continuing use of chemical attacks on civilians in Syria, as well as the proliferation of nuclear weapons. The representative of Peru suggested establishing ad-hoc tribunals to ensure the non-proliferation of nuclear weapons while the representative of Poland suggested creating an international, impartial and independent mechanism (or “IIIM”) to investigate chemical attacks.

Amidst these discussions, tensions were raised while discussing the supremacy of the international law. While many expressed support for compliance with international humanitarian and human rights norms, they also emphasised national ownership of accountability mechanisms. The representatives of the African Union, Cuba and Qatar called for Council members to respect state sovereignty and the principle of equality between States. This was a relevant call in consideration of the ICC and ICJ’s lack of enforcement powers, as well as the widespread impunity generally enjoyed by powerful states. Some speakers further argued that international law should be applied fairly and consistently across all states regardless of their size. As asserted by the representative of the United Arab Emirates, international law’s multilateral rule-based system is vital because it protects smaller states from the abusive powers and hegemony of an elite few.

Lastly, in ensuring international peace and security, other speakers highlighted the need for a greater use of peaceful settlement of disputes, in line with Article 2(3) and Chapter VI of the Charter. The representatives of Portugal, Venezuela and Bangladesh, amongst others, promoted the use of peaceful settlement of disputes, including through negotiation, mediation, arbitration, conciliation, and judicial settlement. The representative of Namibia, for example, shared her country’s successful settlement over a territorial dispute with Botswana through the use of the ICJ as a means of judicial settlement.

Gender Analysis

Out of 77 speakers, only 4 (5%) - the United Kingdom, Norway, Canada and Mexico - referenced the need to ensure that international law and its application respond to the needs of women. The Mexican representative, in particular, reiterated the importance of increasing the number of women mediators in mediation processes during disputes. Meanwhile, the representatives of the UK and Norway called for the Council to prioritise the WPS resolution in pushing for the inclusion of women in post-conflict peace processes. Other speakers highlighted the need to combat impunity for conflict-related SGBV as well as prevent conflicts through early-warning mechanisms.

Prevention

It is notable that 19 speakers (24%) reiterated the Secretary-General’s call of action to focus attention, support and funding efforts towards conflict prevention. The representative of Germany noted, for example, the strong correlation between successful protection of human rights and early warning systems. However, discussions did not go further than this and failed to cover the importance of strengthening international and domestic legal frameworks for post-conflict settings, including to ensure women’s participation, build sustainable socio-economic reintegration programmes, and facilitate disarmament.

Participation

Only the representatives of Mexico and the UK emphasised the importance of the participation of women and women’s groups in the maintenance of international peace and security. The representative of the UK, in particular, called on States to “recognise women’s role in peace and security in line with Resolution 1325”. This is an important call amidst proven data that women’s participation in peace processes increases the likelihood of a peace agreement lasting at least two years by 20% and lasting at least 15 years by 35%. In the same vein, while speakers noted the importance of engaging with regional and sub-regional organisations, none mentioned the importance of working with women’s civil society organisations and other on-the-ground actors to improve the implementation of international law or utilise existing legal frameworks to meet grassroots demands. Consequently, speakers failed to highlight the role of international law in promoting adequate and flexible financial, technical and political support for civil societies and women groups, which would allow them to strengthen capacities and participate meaningfully in high-level discussions.

Relief & Recovery

In spite of a clarion call for justice and accountability for crimes against humanity, only the representative of Canada referenced sexual and gender-based violence (or “SGBV”) as an integral component of most mass atrocities and crimes against humanity. This is concerning in light of the recent debate on sexual violence in conflict held only last month, where many speakers affirmed their country’s commitments towards eradicating impunity for SGBV. That said, Canada referenced SGBV only in the context of the Rohingya crisis in Myanmar. Meanwhile, the Council continues to miss important opportunities to address the prevalence of SGBV as a weapon of war used by ISIL, Boko Haram and other armed actors, as well as the fact that not a single member of these terrorist networks have been held to account for SGBV. Further, although all speakers touched on the importance of combating impunity and ensuring human rights, none addressed the specificity of crimes and human rights violations against civil society advocates and human rights defenders. The Council has to support, through law and in practice, access to justice and accountability for civil society actors and human rights defenders so they would be able to operate free from hindrance and insecurity.

General Recommendations

The current body of international law, the ICJ and ICC systems, among others, already provide room for peaceful settlement to replace violence as a means of dispute resolution. However, these means are often misprioritised and politicised by the most powerful. To effectively fulfill its mandate to maintain international peace and security, as enshrined in the UN Charter, and ensure accountability for all, the Security Council and Member States must:

Strengthen the implementation of international laws and domestic policies, as well as judicial and accountability mechanisms, that address gender inequality and promote women’s full participation in political and communal life;

Curb the flows of small arms by ratifying the Arms Trade Treaty and implementing it through enforced national laws and regulations;

Creating formal mechanisms to transfer women’s demands into the legal and peace processes;

Ensure strong partnerships and meaningful dialogue with women-led civil society, including when Member States are undergoing the review under international human rights mechanisms;

Fundamentally reframe security away from militarised approaches to one based on human rights, sustainable development and equality, in accordance with the Council’s mandate to support peaceful settlement of disputes;

Ensure justice and accountability for all crimes, including SGBV and crimes against human rights defenders and civil society actors by supporting monitoring efforts and consultations with civil societies, women leaders and human rights defenders, and

Increase engagement with UN human rights bodies, including the Office for the High Commissioner of Human Rights (OHCHR) and the Human Rights Council, as a means for better linking between human rights and prevention work.